(Johnson-EU Presidents)[1] – 15 June 2020

The UK’s relations with Europe and “British exceptionalism”

What has the UK learned in the last 46 years?

Introduction

It is now clear that negotiations for a new EU-UK bilateral framework agreement will go “down to the wire” in September or October this year. To judge by any usual standards in modern international “partnership” agreements, agreement on any comprehensive framework text (or series of texts) in time for ratification and implementation in the UK and the EU by 1 January 2021 can be ruled out. But the present situation is unique (certainly not “precedent-based”) and, quite literally, without precedent. The UK is the first EU Member State to withdraw under Article 50 TEU. More importantly, this is the first time in the history of international economic relations that a major country[2] has sought to “de-liberalise” and to diverge from the biggest and most integrated economic area in the world.

Both sides and especially their private sectors would greatly prefer the legal certainty of a new EU-UK legal framework, to further “legal limbo”. The economic damage and additional regulatory uncertainty caused by the COVID 19 pandemic adversely affects both the EU and the UK and increases the urgent need for a lasting settlement.

In terms of power politics, the EU is now, as it was throughout the Article 50 process, in “pole position”. As with the Withdrawal Agreement, the EU Commission was the first to prepare and publish its draft comprehensive text. For its part, the UK – four years on from the referendum – still has no clear idea of the economic content of the new relationship which it seeks with the EU, as an alternative to EU membership. Instead, the UK – under pressure of time and the COVID crisis – relies on a “precedent-based” approach in an unprecedented situation.

The “precedent-based” approach here means that the UK has based its draft texts as far as possible on provisions from existing EU trade or partnership agreements with other third countries, such as Canada, Japan, South Korea and others. As indicated above, this approach presumably derives from an earlier political position taken by the May administration in favour of a “Canada-style” agreement. But as time-pressure has increased during the transition period, it may be that the Johnson Government assumed that, having agreed to certain provisions with other third countries, the EU would automatically accept such provisions with the UK. This assumption is unrealistic not only given the sheer size, diversity and proximity of the UK economy compared, say, with Canada or Japan, but also given the unique challenge of having to fashion a new relationship out of 46 years of legal convergence, with as yet no clarity on the extent to which the UK seeks to diverge from the EU acquis.

The EU will certainly adjust its negotiating position between now and November, starting perhaps with fisheries; but the UK needs to clarify its political[3] and economic priorities in and with the EU and then to devise an appropriate legal framework for these. Precedents, especially in international trade policy, are always helpful; but not the starting or finishing point.

As I write (in mid-June), I find it impossible to envisage that any kind of comprehensive agreement or series of agreements can be negotiated, ratified and implemented by the end of 2020. For there to be no agreement at all would be a massive failure of diplomacy (and politics) on both sides. Ironically, given the services-based nature of the UK economy, a partial agreement is most likely in trade in goods[4]. This would limit damage for economic operators and consumers in the UK and the EU. But the absence of any agreement on trade in services, not to mention sensitive and important areas such as security policy, where WTO (GATS) rules provide a mere shadow of the market access under EU law, would harm the UK far more than the EU.

Two related issues will determine progress (or lack of it) during this summer. These are political will and the setting of pre-conditions. Despite the usual rhetoric on both sides, genuine political will on the EU side has been eroded by the UK’s approach to Brexit since 2016, not to mention the lukewarm support for the European project over nearly 50 years or more. The role and disparaging remarks of the present Prime Minister both before and during the Brexit process are not forgotten or forgiven. The existential challenges facing the EU in the next months and years have pushed relations with the UK far down the agenda.

The recent “troika” meeting chaired by the Croatian Presidency and including Germany, Portugal and Slovenia as the next “troika” mentioned as priorities, the budget and recovery instrument, dealing with persistent migratory flows, the need to strengthen the rule of law, the Single Market especially the digital, climate and trade agendas, social protection, education and research and the accession prospects for the Western Balkans, especially Albania and the Republic of North Macedonia. As far as the UK was concerned, Germany as incoming Presidency mentioned the need for a deal with the UK but “not at any cost”, for example, the level playing field which “was not for negotiation”.

On the UK side, the unavoidable focus on domestic issues (notably economic recovery from COVID 19 and social/racial issues), together with an almost total lack of European expertise at governmental (especially Cabinet) level, do not encourage optimism.

As far as pre-conditions are concerned, fisheries – like agriculture – is a technically complex and politically sensitive sector, out of all proportion to its economic weight, either in the EU or in the UK. If negotiations proceed on a species by species basis, covering both catch and conservation issues, much will depend on the willingness of certain Member States (e.g. France) to pursue negotiations in parallel on other trade dossiers[5]. Data protection is another cross-cutting area identified by the EU where prior agreement is necessary before agreement can be reached on other more economically important subjects.

Agreement on data protection, as on so many other issues, should be facilitated by the UK’s current application of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. However, here – as in other policy areas – the UK’s repeatedly-stated intention to “take back control” and to diverge from the acquis, means that agreement is not a foregone conclusion. As a third country, the UK requires a unilateral decision by the Commission on the adequacy of its national data protection rules. However, the Council’s guidelines provide (para.13) that the Parties’ commitment to ensuring a high level of personal data protection should “fully respect the Union’s personal data protection rules, including the Union’s decision-making process as regards adequacy decisions.”

It is not difficult to see that on this crucial, horizontal, issue – as on the EU’s insistence on UK respect for EU rules on the level playing field – the UK’s political imperative to “take back control” and to “diverge” from the acquis is a major perhaps insuperable obstacle to progress. In addition, the close link between data protection and EU insistence on continued UK adherence to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as well as the “condition, where necessary, to achieve a high level of ambition on law enforcement and judicial cooperation in criminal matters” obviously raise other potential obstacles to agreement.

One final word by way of introduction and in order not to miss the woods for the trees. The single most poisonous factor now as in the past in the UK’s relations with “Europe” is an almost complete lack of trust at political level. Pactasunt servanda should be well-understood by the classicist British Prime Minister!

But the issue is wider and deeper than the UK’s about-turn on its commitments in the Political Declaration. The lack of a coherent, consistent and reliable foreign and European policy by successive UK governments – now compounded by COVID 19, Brexit and a resurgence of unresolved post-colonial problems[6] – is in my view the single most important burden facing the UK today. Sadly, there are unfortunate similarities between Trump’s United States and Johnson’s UK, at least as far as foreign policy is concerned. All of which increases the challenge for “Europe” and the European Project to take and not shirk its responsibilities for future generations of young Europeans.

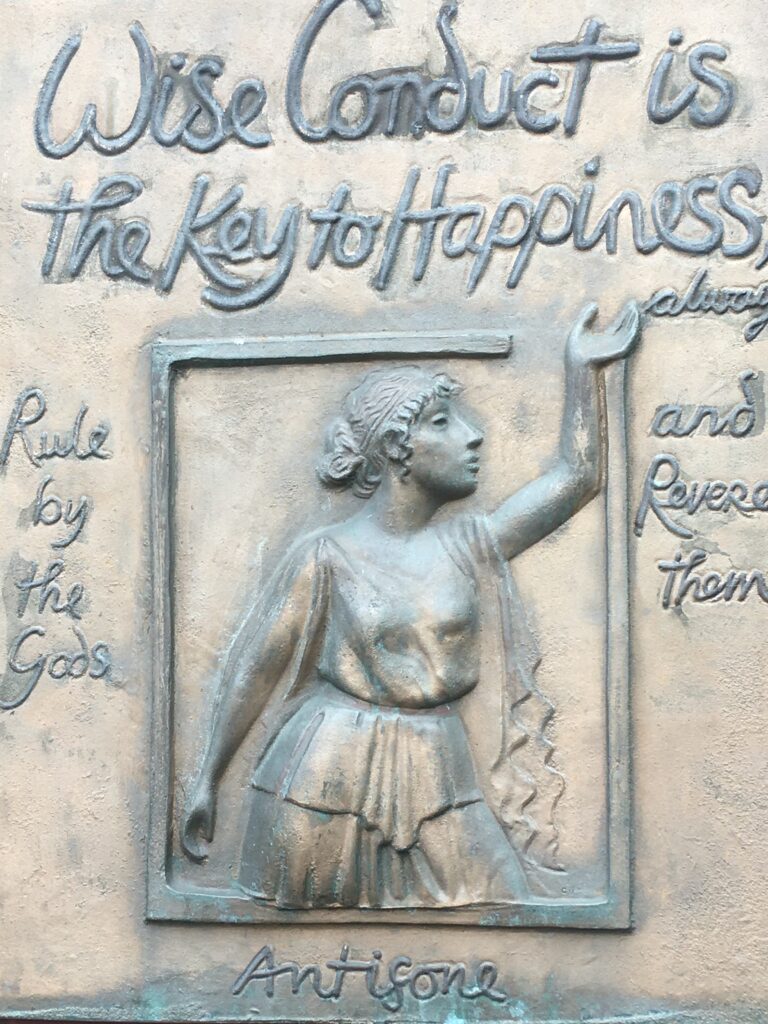

“Wise conduct is the key to happiness. / Always rule by the gods and revere them. / Those who overbear will be brought to grief. / Fate will flail them on it’s winnowing floor / And in due season teach them to be wise” . Oedipus Rex – Burial at Thebes

An extension to the transitional period (TP) can now be ruled out?

Despite the repeated and categorical assertions by the UK[7] that it UK will not exercise its right under Article 132 WA to request an extension of the transitional period, the exacerbation of legal uncertainty which “no deal” represents means that this issue will cause increasing concern as the deadline for agreement draws near. This will be the case above all in the UK but also in the 27 Member States. Nonetheless, the EU-UK statement following the High Level meeting on 15 June stated categorically that “the Parties noted the UK’s decision not to request any extension to the transition period [which] will therefore end on 31 December 2020, in line with the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement”.

In any event, UK primary legislation precludes any request by a UK Minister for an extension. On the EU side, Article 132 (1) of the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) provides that “the Joint Committee may, before 1 July 2020, adopt a single decision extending the transition period for up to one or two years”. It is clear that this will now not happen, at least by the end of June. However, the UK has announced on 12 June that the full application of the UK’s external trade regime will be delayed until (at least) July 2021. De facto therefore, in at least some respects, the status quo (in the UK but not in the EU[8]) will be maintained for at least 6 more months.

Of course, given the necessary political will, UK legislation can be amended by majority vote in the House of Commons and Article 132 WA could be amended by the unanimous agreement of the UK and the 27 Member States. There appears to be little doubt that an extension even for 2 years would have been the clear preference for the EU. Conversely, it is equally clear that the repeated statements by Boris Johnson and other members of his “inner cabinet”, despite the ready excuse of the coronavirus crisis, rule out any request on the UK side.

In any event, the prospect of the UK remaining for two more years (or even one) subject to the entirety of the evolving EU acquis, whilst being excluded from any participation in EU policy-formation or decision-making, would be a form of international humiliation which would be hard for any UK government to swallow.

There are three other reasons why an extension, even if the need for which is of the UK’s own making, would be problematic for the UK. These are that:

- In the context of the coronavirus pandemic, it is clear that the EU like all other international “players” including the UK, will wish to adopt and adapt new rules and procedures in a wide range of sectors (cross-border cooperation on health, the economy, trade, transport, the digital economy, competition including state aids and many others). The formal exclusion of the UK from participation in this legislative process, whilst requiring full compliance, would not be in the interest either of the UK or the EU;

- The UK’s negotiations with important third country partners such as the United States, Japan and others – many of which understandably wish, as a priority, to assess the impact of the EU-UK agreement before finalising their own new bilateral arrangements with the UK – would be hampered and their implementation delayed;

- The political and legal uncertainty which has bedevilled the Brexit process since 2016 would be prolonged even further, making a nonsense of “taking back control”[9], and exacerbating the adverse impact on trade and investment resulting from the coronavirus crisis.[10]

A long hot summer of negotiations? What are the “atmospherics” in London and Brussels now?

On 15 June the high-level meeting to review progress in the negotiations took place between Johnson and the “three Presidents” (VDL, Michel and Sassoli). Even if it had not been “virtual”, it would have been difficult to envisage much conciliation between Johnson’s blustering attempt to hide his lack of “grip” on detail and the cool confidence of the EU triumvirate, resting on their “mandate”, confident (for the moment) of the support of all Member States and with a “tried and tested” negotiator in Michel Barnier.

In looking to the next 3 or 4 months, including the traditional European “closedown” in August, however, it is important not to see the meeting on 15 June in isolation, but as one step along the road travelled since 23 June 2016.[11] At least, there was no “walk out” by the UK Prime Minister. Although the text of the statement following the high-level meeting on 15 June appears banal (and even in some respects disingenuous in referring to 4 rounds of “constructive” negotiations), agreement was reached on a further series of negotiations in July and August.[12]

On the level playing field and other “principles” underlying the agreement, the text provides that the Parties should “intensify the talks in July and create the most conducive conditions for concluding and ratifying a deal before the end of 2020. This should include, if possible, finding an early understanding on the principles underlying any agreement”. The text also confirms the Parties’ commitment to “the full and timely implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement”. On the EU side, it may be assumed that this refers especially to the citizens’ rights and Irish border parts of the WA, where doubts exist on the adequacy of current UK efforts to implement the WA.

The tone[13] of Barnier’s assessment of the third and fourth rounds of negotiations – reading between the lines.

Barnier’s “remarks” on Friday 15 May 2020 cover three pages and are sufficiently explicit to make abundantly clear the yawning gulf – both conceptually and on substance – between the parties. “The EU wants a modern, unprecedented, forward-looking agreement. Not a narrow one rooted in past precedents and sliced up sector by sector.”[14]

It would be an exaggeration and certainly undiplomatic to say that Barnier spoke with contempt for the UK, its political leaders and his negotiating partners. He paid tribute to the “professionalism” of the 500 civil servants[15] who participated “virtually” in 11 Working Groups and acknowledged the difficulty caused by the absence of informal, face-to-face, direct and discreet contacts between negotiators.

Listening to Barnier’s presentation, for the most part in French, left little doubt about his disdain for the UK’s approach to the negotiations. The growing “erosion of trust” felt by the EU for the UK and for Johnson and his Cabinet in particular, which is so essential to any international negotiation and to the implementation of any international agreement, was clear. The fact that the UK Prime Minister has rowed back on his commitment in the Political Declaration to include level playing field provisions in the agreement is the most damaging example of this.

My personal view is that this volte face by the UK Prime Minister and his Government has soured not only the atmosphere in the negotiations themselves between David Frost and Barnier and the senior members of their teams, but also the reputation of the UK more widely, in the von der Leyen Commission (for example in the Joint Committee chaired by Vice President Sefcovic and Michael Gove), but also in the Council[16] and in the European Parliament.[17]

Finally, the language used by Barnier in his press conference was, in my view, unlike that which would normally be used in describing the state-of-play with other third countries and reflects his personal frustration and that of his team with the UK’s approach to negotiations. He spoke in French of “les britanniques” rather than “the UK”. He said that the only progress had been on fisheries, with “no progress at all on other subjects”. This had been a round “of divergence with no progress”.

The EU respected UK sovereignty and its decision to leave the EU to become a third country; but the UK, for its part, had to respect the EU’s sovereignty, especially as regards its Single Market and Customs Union. The UK had to “live up to the Political Declaration signed by Boris Johnson”. Respecting the “non-regression” clause (i.e. the commitments on the level playing field in paras. 17, 21 and 77 of the Declaration) was a matter of fundamental principle for the EU and not “a matter of negotiating tactics”.

In conclusion, Barnier said that he was “determined but not optimistic” about reaching agreement. He said that the UK were “unrealistic” in seeking “all the advantages and none of the obligations” of being a Member State. The Single Market was the EU’s “greatest asset” and it would never be sacrificed to satisfy the UK’s demands. In the Brexit process, the UK had “under-estimated the costs and difficulties which would arise as a result of the re-imposition of controls at the frontier”.[18] Similarly, on financial services, Barnier said “there would never be any question of co-management”, since access to the EU’s financial services market was the exclusive (“autonomous”) competence of the EU. If the outstanding differences could not be resolved, there would be no question of a “sell-out” (“un accord brade”) by the EU; there would rather be no agreement at all. The EU had issued more than 100 notices to economic operators in the EU in order to prepare for just such an eventuality, including 6 on digital trade in the last week.

Why do British politicians still not understand the EU?

It is extraordinary that in the UK, 46 years after accession in 1973, there is still so little understanding of the European Union, its institutions and procedures, of the European Project and – perhaps most important of all – the way in which the EU deals with “third countries”. [19] The present situation is of course unique, in the sense that this is the first time that the EU has had to “re-negotiate” a new relationship with a former Member State. However, faced with a novel situation in 2016 after the UK referendum, the EU quickly implemented Article 50 TEU, using procedures which were broadly analogous to those deployed under Article 207 TFEU for the common commercial policy. From the outset therefore, in March 2017, the UK has been treated – in fact if not in law – as a “third country”.

Apparent ignorance of the unique “personality” of the EU by present and past UK politicians is deeply ironical. In sharp contrast to persistent political agnosticism about the European Project[20] in the UK, the legal profession (Bar, solicitors and judiciary) and academics have played a prominent part in the development of EU law. Similarly, without exception, British Commissioners[21], European judges and Advocates General and many MEPS (though not of course Nigel Farage and his cronies) have gained the respect of their European peers. Despite a consistent lack of commitment to the European Project, with “opt-outs” and derogations from many major policy areas, the UK managed to retain the respect and even affection of many of its partner Member States at least in my judgement till 2015.[22]

Gross over-simplification notably by the print media[23] of the European Project in the UK, combined with “British exceptionalism” are, in my view, at the root of the UK’s failure to come to terms either with EU membership or – more dangerously, with the Union as the UK’s most important international partner. Over-simplification in my view includes constant references to “Brussels” or “the bloc” and a failure to understand the role played by the various individuals and Institutions, in this unique and unprecedented experiment[24] in international relations.

In the current negotiations, as in the Article 50 process, for example, the importance of the role played by Michel Barnier as head of the Commission Task Force, has been greatly exaggerated. Of course, as a former French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Agriculture and Fisheries and a former Commissioner for Regional Policy and the Internal Market, as well as Head of the Task Force for the Article 50 negotiations, Barnier has immense experience of a wide range of EU policies. He has clearly earned the trust of all Member States, has a direct line to the French President, as well as Charles Michel in the European Council and other heads of government, and has already built trustful working relations with the new European Parliament.[25]

Nonetheless, decision-making on the new agreement(s) with the UK rest with the Member States in the Council and with the European Parliament. This is why – both in the Article 50 process and the current negotiations – Barnier is in daily contact, before, during and after each negotiating round, with national capitals and the Parliament. And, of course, Barnier is “merely” an employee of the Commission with the status of a Director General. Thus, in law and in fact, he reports to President von der Leyen and her College.

The crucial role played by the 27 Member States, individually, in groups and as an Institution in the Council, backed by the – unseen but powerful – Council Secretariat in the EU’s external relations, also appears to be under-estimated by London. Given the UK’s attachment to “sovereignty”, it is strange to assume that other European States do not value their own independence just as highly.[26] All Member States are acutely aware of “keeping control”[27] over all aspects of their internal and external relations. However, all have equally recognised that in a highly volatile world where – irrespective of political will – national frontiers are increasingly irrelevant and events tend to be dominated by a few major powers – “classical” sovereignty is more effectively exercised in cooperation with others.

Thus, the long-standing issue of legal competence or rather the scope of exclusive competence in external affairs[28], remains relevant, but much more complicated, today. The Commission will still have recourse to the European Court to assert exclusive EU competence where this appears both justified and beneficial to the external defence of EU law and policy.[29] More frequently however, irrespective of the legal position, the Commission and Member States may agree that it is in the EU’s political and economic interests to take a common position in negotiations (or in the implementation of an agreement) with a third party. This is certainly the case with the UK, both in these negotiations and, later, in the implementation of any agreement reached.

In the case of the Article 50 negotiations, the Council agreed with the Commission’s proposal that the Withdrawal Agreement and related Political Declaration would be negotiated with the UK, exceptionally, as a matter of exclusive EU competence. Any attempt by the UK therefore to divide and rule as between Member States was ruled out.

Similarly, in the present negotiations, it is clear that Member States have a wide variety of differing though not necessarily conflicting, interests in trade and other relations with the UK. Until the content of any final agreement(s) is known, it is impossible to say whether it will fall within the exclusive competence of the EU or not. It is however certain that the 27 will maintain political solidarity in these negotiations, even in matters falling within mixed or national competence.

Key points in Barnier press conference on 15 May 2020

- the UK did not engage in a real discussion of the level playing field and “fair play” rules we agreed to with Boris Johnson in the Political Declaration;

- this was a round of divergence with no progress;

- no progress on the single governance framework;

- UK lack of ambition on issues such as the fight against money-laundering and the inclusion of roles for Parliament and civil society in the future agreement;

- Absence of UK commitment on the European Convention on Human Rights;

- UK insists on lowering standards on data protection;

- Barnier (as head of the Task Force) has the explicit support of President Sassoli (European Parliament), von der Leyen (Commission) and Michel (European Council);

- Our trade relationship will never be as fluid[30] as in a Single Market or Customs Union;

- With a neighbouring country which is inter-connected with and a former Member of our Union, it would be totally artificial to copy-paste a “best-of” from existing FTAs with Canada, South Korea or Japan;

- We are no longer in the 70s – trade must support sustainable development and climate change;

- The agreement must protect social, environmental standards as well as address state aid and taxation;

- Reinstating tariffs and quotas has not been seen in decades and will not free the UK from level playing field obligations – the Union does not want such an anachronism;

- Open and fair competition is not a “nice to have” it is a “must have”;

- Why would we give access to our market to UK professionals when EU fishermen are excluded from UK waters?

- Why would we help UK enterprises provide services in the EU without any guarantee of fair play?

- Why would we be ambitious on extradition or exchange of personal data without guarantees on the protection of human rights?

- How can we guarantee that our partnership would work without a single institutional framework?

- The UK is looking to maintain the benefits of a Member State without the obligations (e.g. complete free movement and stays for short-term providers of services); to maintain existing arrangements on electricity supply; to assimilate UK auditors to those in EU; to maintain a system of mutual recognition of professional qualifications (MRPQ) that is the same as in the EU;

- The EU is not willing to co-decide equivalence on financial and other services;

- This is not an opportunity for the UK to “pick and choose”;

- There is still in the UK a real lack of understanding about the objective and sometimes the mechanical consequences of the British choice to leave the Single Market and the Customs Union;

- There are still issues on the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement (e.g. citizens’ rights issues on both sides and the Irish Protocol, where the UK has still not laid out its approach)[31].

The Frost-Barnier letters of 19 May 2020 – hardening positions.

Frost makes four key points:

- The UK is looking for “a suite of agreements with an FTA at the core”. The UK’s legal texts “draw on precedent where relevant precedent exists and pragmatic proposals where it does not”.[32] It is “perplexing that the EU insists on additional, unbalanced, and unprecedented provisions in a range of areas, as a precondition for an agreement”;

- On goods, the EU will not even replicate provisions in other agreements on mutual recognition of conformity assessment, sectoral TBT arrangements for cars, medicinal products, organics and chemicals, or equivalence measures for SPS.[33] On services, the EU resists regulatory cooperation of financial services and reduces the time for short-term stays for business visitors.[34] “We find it hard to see what makes the UK, uniquely among your trading partners, so unworthy of being offered the kind of well-precedented arrangements commonplace in modern FTAs”.

- On the level playing field, the UK text “sets out a comprehensive set of proposals to prevent distortions of trade and unfair competitive advantages”

- The EU text contains “novel and unbalanced proposals which would bind this country to EU law or standards and would prescribe the institutions we would need to deliver on these provisions.” An “egregious example” is EU state aid rules and an enforcement mechanism which “gives a specific role to the ECJ”. “You must see that this is simply not a provision any democratic country could sign, since it would mean that the British people could not decide our own rules to support our own industries in our own Parliament”. “We cannot accept any alignment with EU rules, the appearance of EU law concepts, or commitments around internal monitoring and enforcement that are inappropriate for an FTA.”

Further points made by Frost are that:

- If the EU’s demand for a level playing field is based on the complete abolition of tariffs and quotas, the UK would be prepared to discuss less than that (i.e. the partial abolition of tariffs and NTBs), which would only complicate and prolong negotiations on trade in goods:

- The level playing field demand is not justified on economic terms;[35]

- The level playing field in not justified on grounds of “proximity”[36];

- On fisheries, EU access to UK waters after the TP remaining the same is not realistic;

- The EU’s governance proposals are not replicated in any other EU agreement;

- On criminal law enforcement, putting a set of standard measures in a single agreement cannot justify the exceptional and intrusive safeguards the EU are seeking.

“Overall, at this moment in negotiations, what is on offer is not a fair free-trade relationship between two close economic partners, but a relatively low-quality trade agreement coming with unprecedented EU oversight of our laws and institutions.”

Barnier’s reply also makes 3 key points – re-stating the position set consistently by the Council since 2017

- In October 2019 a Political Declaration was agreed by the UK Prime Minister. This is the only precedent the EU is following[37]. The EU and the UK are equally sovereign and set conditions for access to their markets. There is no “automatic entitlement” to any benefits the EU may have offered to other partners, in “other contexts and circumstances”. Every agreement is unique. “We do not accept cherry-picking from our past agreements. The EU is looking to the past and not the future in these negotiations”.;

- “The UK cannot expect high-quality access to the EU Single Market if it is not prepared to accept guarantees to ensure that competition remains open and fair. This means upholding common high standards at the end of the TP in state aid, competition, social and employment standards, environment, climate change and relevant tax matters. This does not mean that the UK will be bound by EU law after the TP; the UK will be free to set its own higher standards. But we need to give ourselves concrete, mutual and reciprocal guarantees for this to happen.”;

- On law enforcement and judicial cooperation, “the EU has never offered such a close and broad security partnership with any third country outside the Schengen area”. The UK seeks access to EU and Schengen data-bases, but this is limited to the obligations Member States have. We also need the UK to provide strong safeguards on the protection of fundamental rights, as agreed in the Political Declaration, such as adequate data protection standards.

It is understandable, given the tone and content of these letters, which must be rare if not unprecedented between negotiators for a trade agreement, that there was pessimism on both sides as regards possible progress in the fourth round of negotiations, or indeed for a successful conclusion at all in 2020. The practical and logistical difficulties posed by the COVID 19 crisis and which may not be resolved until the autumn (if then) clearly do not facilitate relations between negotiators and their teams.

However, the acrimonious and vindictive tone of these negotiations, which I have never previously witnessed derives exclusively from the UK side.[38] Not from the decision to withdraw itself, even if the political wisdom of an “in/out” referendum was questioned by many European politicians. Rather from the way in which successive UK Governments (Cameron, May and Johnson) have managed or rather mismanaged the process internally and externally. The poison which infuses UK attitudes to “Europe” is destined to affect not only the present negotiations, but also bilateral and multilateral relations between the UK and the EU for years to come.

Barnier press conference on 5 June 2020 (following the fourth round).

Predictably, in another wasted week, little or no progress was made in negotiations. In a tone more of resignation than bitterness or vindictivenesss (and observing the usual formalities[39]), Barnier summarised the key outstanding issues, whilst keeping hope alive “if we keep our mutual respect[40], our serenity and our determination, I have no doubt that we will find, in the course of the summer or by early autumn at the latest, a landing zone between the UK and the EU.”

Even if progress in any meeting tends to be slowed in a “virtual” setting and time in such meetings passes quickly, it is hard to imagine how 11 Working Groups, comprising over 200 officials, managed to fill four working days, when positions on almost every item diverge radically.[41]

The almost total absence of progress is unsurprising given the EU’s[42] accusation of bad faith or at least the absence of good faith on the part of the UK in general and Boris Johnson in particular. Good faith and respect for international agreements (pacta sunt servanda) are arguably the oldest and most fundamental principles of public international law. Barnier’s press conference was dominated by repeated references to the Political Declaration (PD) attached to the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) of 17 October 2019.

The binding nature of the Political Declaration – a test of trust and good faith for the UK

Though not formally binding in law, in contrast to the WA itself, the PD is based on Article 50 TEU and is entitled “Political Declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the EU and the UK”. It provides in its introduction[43] that “this declaration establishes the parameters of an ambitious, broad, deep and flexible partnership across trade and economic cooperation with a comprehensive and balanced Free Trade Agreement at its core, law enforcement and criminal justice, foreign policy, security and defence and wider areas of cooperation. If the Parties consider it in their mutual interest, during the negotiations, the future relationship may encompass areas of cooperation beyond those described in this political declaration.” Crucially for the EU, the PD[44] provides that the balance of rights and obligations must “ensure the autonomy of the Union’s decision-making and be consistent with the Union’s principles, in particular with respect to the integrity of the Single Market and the Customs Union”.

The fact that Johnson himself personally claimed credit for securing changes in both the WA, notably the Protocol on the Irish border, and the PD previously negotiated by Theresa May and her team, makes it all the more difficult now:

- To explain why the UK appears to refuse even to negotiate[45] on the issues comprised in the concept of a level playing field;

- To see how, even in a political meeting between Johnson, von der Leyen and Michel some “bridge” might be found, without Johnson being accused by the Brexiteer MPs and his principal unelected political adviser of selling out to the EU; and therefore

- Especially given the volume and complexity of outstanding issues, even in a “reduced” agreement, and the very short time now left for negotiations, to envisage anything other than a “no deal” situation on 31 December 2020.

The good faith issue is crucial not only because its absence completely undermines the credibility of the UK in these negotiations, but also because of the shadow which it casts on respect for and implementation of any future agreement with the EU and with other third countries. The UK’s approach in these negotiations, coinciding with or closely following issues such as Johnson’s defeat in the Supreme Court on the prorogation issue and the role of his political advisor Dominic Cummings in the coronavirus crisis, damages the UK’s often self-proclaimed attachment to the rule of law[46] in international relations.

The undermining of trust in the UK’s willingness or ability to respect its commitments in national, European or international law is compounded in the present negotiations, by fears in the EU that the UK in general and Johnson in particular is not seriously committed to ensuring the effective implementation of the WA and its Protocol on the Irish border.[47] Finally, the fact that the UK have still not committed unequivocally to remain a party to and to implement faithfully the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), scarcely reinforces confidence in the EU Institutions and 27 Member States, in the UK’s reliability in areas such as civil and criminal justice cooperation.

Four “big sticking points”.

Against this grim background, Barnier identified four major outstanding and “cross-cutting” issues as follows:

- Fisheries (agreement here being a pre-condition to agreement on trade), where the UK “showed no real willingness to explore[48] other approaches than zonal attachment on quota sharing, continuing to condition access to its waters to an annual negotiation, which is technically impossible for us”;

- Free and fair competition (the level playing field), where “we didn’t make any progress, despite choosing to focus this week on issues which should have been more consensual, such as non-regression mechanisms on social and environmental standards, climate change, taxation or sustainable development”;

- Guarantees on people’s fundamental rights and freedoms needed to underpin close police and judicial cooperation[49]; and

- The governance of the future relationship, where “we were unable to make progress on the issue of the single governance framework establishing legal linkages between our different areas of cooperation.”

As for the EU’s position on these issues, Barnier said that “we are asking for nothing more than what is in the Political Declaration”.

Unlike his wide-ranging substantive comments following the third round of negotiations, on this occasion, having outlined the four key outstanding issues, Barnier focussed on the UK’s backtracking from the PD and failure yet to correctly implement the Irish Protocol in the WA.

Is the UK even prepared to negotiate – for example on “level playing field” issues?

Although EU allegations of bad faith are undoubtedly the most serious cause for concern, equally worrying is the apparent unwillingness of the UK even to negotiate. Especially in negotiations involving an EU composed of (now) 27 sovereign States[50] – compromise is indispensable in order

- To agree a “mandate” for the EU’s negotiator amongst the 27 Member States, with input from the Parliament and other “stakeholders”;

- To reconcile the requirements of the “mandate” with the “demands” of the other Party (also subject to its own “mandate”); and

- To secure the agreement of 27 Member States and the European Parliament[51] to the resulting compromise legal text.

I have no doubt that the EU is ready to negotiate and to reach compromise solutions on many if not all outstanding issues, even those classed as “level playing field” issues.[52] The problem is of course that, having accepted EU standards for the level playing field as a Member State, it is more difficult for the UK now, as a non-Member, to convince the EU that it has devised alternative standards which achieve the same effect (e.g. of consumer, investor, environmental or nuclear safety) as those in force in the EU.

For the Commission, negotiating changes to the “mandate” with 27 Member States and the European Parliament is certainly a challenge in every bilateral and multilateral negotiation. However, in this unique case, the principal difficulty facing the EU has been unchanged since the Article 50 process started in March 2017. This is the total lack of preparedness on the UK side leading to:

- A Withdrawal Agreement drafted almost entirely by the Commission, focussed, in accordance with the Council mandate, on the protection of the EU’s interests;

- An “aspirational”, but potentially far-reaching, Political Declaration, which – from a UK perspective – appears to have melted like a iceberg in the sun between October 2019 and the start of negotiations in February 2020;

- A continuing absence of clarity on the UK side on the structure and above all content of the alternative arrangement for relations with the UK’s most important trading, investment and security partner, more than three years on;

- The EU once again having taken the lead in negotiations by settling and publishing its mandate 2 months ahead of the UK;

- Continuing political and legal uncertainty for economic operators (traders, investors and citizens) both in the EU27 and in the UK – a situation massively compounded by the COVID-19 crisis.

For the UK simply to refuse to negotiate other than by tabling an amalgam of uncoordinated “vertical” and sectoral texts compiled on the basis of “copy and paste” from the EU’s agreements on the grounds that the EU’s position is “dogmatic” is unrealistic. A series of new initiatives from the UK, setting out rational alternatives to the EU’s proposal, is the only way to break the current deadlock.

As things stand, the EU is negotiating from a position of relative strength[53]. Quite apart from its dominant position as the world’s largest economic area (notwithstanding all its monetary, fiscal and macroeconomic weaknesses, greatly exacerbated by COVID-19), the fact that in the absence of an agreement the EU will simply treat the UK as any other “third country”[54] without a preferential regime under GATT Article XXIV, means that little or no change is required to the EU’s external economic policy. Added to this is the fact that the EU has had ample time to prepare more than 100 contingency measures to minimise the damage of a “no deal” outcome.

The UK on the other hand:

- Is bound by the totality of the EU acquis under the transition arrangements in the WA until 31 December 2020;

- Is bound by the Withdrawal Act 2018 to maintain in force the entirety of the EU acquis as UK rather than EU law from 1 January 2021, in the absence of any extension to the WA;

- Has yet to define how, in what areas and to what extent it intends to diverge from the EU acquis with effect from 1 January 2021 and consequently

- Remains in “legal limbo”, with no clear end in sight. “Trade on WTO terms” – sloganized misleadingly by the UK as an “Australia-type” situation – is certainly not the legal certainty sought by the UK private sector and especially not in trade in services.

The fact that, meanwhile and notwithstanding the COVID-19 crisis, the UK is progressing in negotiations with other trading partners, such as the United States and Japan, presumably on terms which differ significantly from its current regime based on the EU acquis, greatly complicates planning for traders and investors[55], as well as negotiations with the EU.

As Barnier said on 5 June, “round after round, our British counterparts seek to distance themselves from this common basis”. Barnier gave four examples of this “distancing”:

- PD para. 77 – “given our geographic proximity and economic interdependence” our future agreement must encompass robust commitments to prevent distortions of trade and unfair competitive advantages (the “level playing field”) – “we are today very far from this objective”);

- PD para.66 – “Prime Minister Johnson agreed to maintain our existing high standards of nuclear safety” – “we are very far from this objective”;

- PD para.82 – “Johnson agreed that our agreement should cover anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorism financing” – “we are very far from this objective”;[56]

- PD para. 118 – “Johnson agreed to base our future relationship on an overarching institutional framework, with links between specific areas of cooperation.” – “We are, once again, very far from this objective”.

Finally, in the fourth round, the UK “has refused to talk about our cooperation on foreign policy, development and defence, even though we agreed this with Boris Johnson in the PD.”

Questions in Barnier’s press conference after the fourth round on 5 June 2020

On state aids, one journalist referred to Frost’s letter referring to “a particularly egregious example [where the UK would be] required simply to accept the EU state aid rules [which] would enable the EU, and only the EU, to put tariffs on trade with the UK if we breached those rules; and would require us to accept an enforcement mechanism which gives a specific role to the CJEU”. In reply, Barnier merely said that each side was “sovereign” (impliedly also on subsidies) but that the EU wished to be protected against “dumping” and “unfair trade”. Barnier did not say (but it is the case) that the EU in any event has the right under GATT Articles VI and XVI to take action against unfair trade from any trading partner[57]. All EU preferential trade agreements have provisions to deal with unfair trade. A possible role for the CJEU is a matter for negotiation.

On the Irish Border Protocol, Barnier was asked whether it was being used, cynically, as a “bargaining chip” by the EU in negotiations? Barnier said that both sides had worked on this highly sensitive issue “day and night” for more than 3 years. The problem was created by the UK with Brexit; not by the EU or Ireland. There were 4 issues at stake: 1) preserving the Good Friday Agreement; 2) preserving to the maximum North-South cooperation; 3) protecting the integrity of the Single Market; 4) preserving “democratic legitimacy” in Northern Ireland.

The current text of the Protocol was agreed with Johnson personally and now needed to be implemented before the end of 2020. There were already controls in many ports and in Belfast. Work was continuing on all the technical issues involved and the alternative to agreement was a hard border. We need “technical commitments from the UK, which is not the case today”. As a pragmatic politician who had visited Northern Ireland (Dungannon) and who thoroughly understood the problems there, Barnier understands the “spin” being given in parts of the UK press on this issue, “which is quite wrong”.

Barnier was asked about an urgent need for a high-level UK-EU meeting to resolve the impasse. He said it was already fixed. “Boris Johnson has already made commitments in the PD. This is the only precedent we need.”

On fisheries, Barnier was asked if the “maximalist” EU position was open to compromise? He said (as a former French fisheries Minister) that this was a very complex area involving more than 100 species, and involving biodiversity and conservation as well as catch quotas. But the EU’s “pre-conditions” on fisheries and the level playing field had been on the table now for 3 years. UK sovereignty on fishing in its waters was acceptable, but to re-negotiate quotas every year was not. So far, the UK had not even been willing to open negotiations.

The bigger picture – the UK in the world (1945-2045) – Brexit and “British exceptionalism”[58] ; “making Britain great again”.

1945, 1973 and 2020 are three landmark dates in the history of the UK – the renaissance of Europe after the Second World War, joining and then leaving the European Project. By any standards, the European Project has been a success in contributing (with NATO) to the longest period without war[59] in Europe for centuries. The physical[60] scars of the two most destructive wars in history have largely been healed. Europe has largely[61] been reunited on the basis of the fundamental values set out in the UN Charter, the ECHR and the EU Treaties.

The UK, like most other EFTA countries[62], joined the European Project not as a purely economic project but with a clear political aim[63]: not to create a United States of Europe, but rather a unique and unprecedented form of cooperation based on solidarity, in which European, national and regional identities could be combined so as to guarantee to the greatest extent possible political stability, the avoidance of conflict and economic prosperity.

In one sense, the political decision to withdraw from the EU is a gamble: that the UK will “do better” as an “independent” State outside the legal framework of the EU. One motivation for leaving, might have been that the Project was on the point of collapse. However, UK Prime Ministers have repeatedly stated that they hope that the European Project would succeed, at least economically, not least because of the heavy dependence of the UK on the biggest market in the world. In fact, it now appears to be undisputed by the current UK Government, that even without the damage caused by the COVID 19 crisis and even if a new economic arrangement is reached with the EU, the UK will suffer serious economic harm as a “third country”, at least for the foreseeable future. Withdrawal therefore is purely a political matter: to re-assert UK sovereignty without the legal and political constraints of EU membership.

“Sovereignty”, in the sense of self-government, freedom from external control and the preservation of fundamental values[64] is of course (literally in many cases) a matter of life and death for all States and many sub-State entities. Nobody would deny the importance of sovereignty to the Baltic and Balkan States which gained or re-gained independence in the last 30 years and all of which now play a leading role in the European Project.

In deciding to withdraw from the EU, it would be foolish to suggest that the UK has, uniquely, discovered (or re-discovered”) a magic formula which will somehow guarantee a return to former glories. Nonetheless, both during the UK’s membership and now that it has withdrawn, there are suggestions that in some way the UK is unique or “exceptional” in today’s global community.[65] Claims that by leaving the EU, the UK will “take back control” and “become great again” carry unfortunate echoes of Trump’s United States. In this context, at least for the 66.65 million inhabitants of the UK (as well as more than 2 – 3 million UK citizens living abroad[66]), in particular the younger generation, the crucial issue is what difference a “sovereign” UK will make to their everyday lives. Sadly, at no time before, during or since the referendum in 2016 has any UK Government defined with clarity the alternative to EU membership, either with the EU itself or with partners around the world, including the United States and the 54 countries in the Commonwealth.. Thus, the last five years have been (and still are) characterised by almost total legal uncertainty.

The unforeseen COVID 19 pandemic has now added a new dimension to the multiple challenges facing the UK and created by withdrawal from the EU. It illustrates the irrelevance of national frontiers, not only in health but in most other policy areas, in a world transformed by the revolution in technology and communications.

British “exceptionalism” is of course a subject far beyond the scope of a paper dealing mainly with the current state-of-play in the withdrawal negotiations. However, the fact that there is an intrinsic link between the domestic and international aspects of most issues where the UK is now seeking a new “identity” outside the EU, means that it is helpful to identify some aspects of this phenomenon here. In my view, these are relevant not only in the context of UK withdrawal from the EU, but also because they will shape the UK’s future, both internally and internationally.

“British Exceptionalism”.

“British exceptionalism” has been defined as the idea that Britain is inherently different from, and superior to, other nations and empires.[67] The Brexit process has undoubtedly brought a spate of literature on the subject.[68] Many writers link the spirit of “exceptionalism” to the UK’s imperial past, comparing the catastrophic handling of Brexit (“grand aspirations undercut by slapdash and delusional strategic planning”[69]) with other milestones in Britain’s imperial past such as the Amritsar massacre (1919), the creation of the Irish Free State (1922), the partition of the Indian sub-continent (1947), the arrival of the Empire Windrush (1948), Suez (1956) and the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong (1997). When the UK left the EU at the end of January 2020, Johnson declared that “ a newly-forged UK was embarked now on a great voyage, a project that no one thought in the international community that this country would have the guts to undertake.”

As discussed in more detail below however, Britain’s sense of economic invulnerability of puzzling. “Much of the British elite know little about how Britain’s economic strengths and vulnerabilities compare with other European countries.” [70] Although the UK is the on paper the 6th largest economy in the world, three-quarters of the country is poorer than the EU average and there are now very few UK-owned companies with a strong record of growth.[71]

Key elements of “British Exceptionalism”.

There are perhaps at least three major factors which distinguish the United Kingdom more than others from its 27 former partners in the EU, as well as others around the world.

The first is the fact that the United Kingdom brings together four “nations”, each with its own identity, history, identity, culture, political structure and, to a certain extent, language[72]. England and Scotland were, comparatively recently[73] sovereign States, although this was never the case for Wales[74] or Northern Ireland. Unlike any other State in the United Nations, the UK also has political and legal responsibility for more than 20 overseas territories. This “fragmentation” of UK sovereignty lacks any written and over-arching constitution to bind this disparate country together.

The second is that, unlike most of its continental European neighbours and important partners like Japan, the UK escaped occupation and wholesale destruction during the Second World War[75]. Rebuilding from scratch, as was the case in Germany and Japan for example, was unnecessary. Perhaps even more important, unlike (for example), France, the Benelux, Denmark and the former Warsaw Pact countries, the UK has not had to heal the scars of occupation and alleged collaboration with an enemy power.

Finally, and this does have an immediate bearing on UK foreign policy since 1945, now and in the immediate future, for almost 300 years, England, Great Britain and the United Kingdom have (successively) been the greatest[76] imperial power the world has seen. This period of UK history ended, with independence for former colonies[77], between 1947 and 1970.

Thus, at the risk of over-generalisation, the UK’s accession to the European Project in 1973 represented a “turning in the road”, looking rather towards our European neighbours rather than outwards across the sea to the Empire and the United States.[78] Now, after 46 years of unsettled and sometimes half-hearted membership of the European “club”, once again the UK seeks to become a “global” power. Arguably, this historical change has been (and still is) more of a challenge for the UK than for example, for continental countries devasted not only by the Second World War but also, in the case of former Warsaw Pact countries, by living under the yoke of the Soviet Union for 45 years or more.

Other aspects of “British exceptionalism” affecting the UK’s past, present and future role in and with Europe and in the world.

1.The failure of the UK to recognise and adjust to its consistent economic decline since 1900 relative to other countries (initially Germany and the United States). One specific weakness in the UK economy today is the virtual absence of any UK ownership of manufacturing capacity in any important sector, combined with the fact that foreign investments in UK manufacturing[79] were made with an eye to securing market access in a frontier-free Single EU Market;[80] the UK therefore lacks “control” over these sectors precisely at a time when it has also severed market access to its largest export market for services.[81]

2.The flaws in the constitution and governance of the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”, highlighted by the fragmentation of the UK not only in the Brexit process[82] but also, now, in the management of the COVID 19 crisis[83]. Other constitutional issues highlighted by the Brexit process include the partially unwritten and convention-based nature of the Constitution[84], the relationship between the executive, legislature and judiciary[85], the role of the unelected House of Lords[86], the status and function of the monarchy[87] and the electoral system[88].

3.The illusion of “great power” status as a result of “winning” two World Wars to which, however, the failure of UK foreign policy between 1900 and 1914 and between 1930 and 1938 contributed significantly and where “victory” was only possible as a result of the contribution of other Powers (notably the United States and the Soviet Union).

4.The entirely legitimate remembering and honouring of the sacrifices made during two World Wars and other conflicts[89], but without the trauma of those conflicts being “embedded” in the British psyche as is the case in (for example), Germany, France, the Benelux countries[90], Japan, China and those Asian countries which suffered under Japanese occupation in the 1940s.

5.The dismantling of the British Empire from 1947 onwards, at the insistence of the United States[91], and the failure to make best use of the Commonwealth as a global force for setting and maintaining fundamental values, as a preferential trading area under GATT Article XXIV and, following UK accession to the EC in 1973 as a reinforcement of a united Europe’s global presence.[92]

6.More generally, a failure to build constructively – and in cooperation with European allies – on the UK’s historical and mainly colonial relations with now-independent countries, including Ireland[93], Malta[94], Cyprus[95] and Spain[96], the UK’s former colonies in Africa[97], in the Asia-Pacific region[98], the Middle East[99] and the Indian sub-continent and neighbouring countries[100]. To these may be added the UK’s more than 20 Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies around the globe.[101] Whilst the UK obviously cannot be held responsible for ongoing conflicts in all the countries, territories and regions in which it has played an important role in the past, it is nonetheless arguable that the UK’s ongoing relations with these entities could have been stronger and more influential as a “lead Member State” of EU foreign, security and defence policy than, as is now the case, independently.[102]

7.The failure of successive UK governments since the 1950s to manage immigration (especially as a result of decolonisation but also EU citizens), in such a way as to ensure the greatest possible assimilation of different racial, ethnic and religious groups into the community, thereby pro-actively promoting equality in every sense of the word.[103]

8.The illusion (or at least the exaggeration) of a “special relationship” with the United States (another country with an historic colonial relationship with England). Apart from linguistic ties[104] and a military-security relationship deriving principally from 1945 and the subsequent Cold War, the relationship between Washington and London has not been (and could not be) one between equal partners. The current negotiations for a new bilateral relationship between the UK and the US will be a “moment of truth”, when – in many areas – the UK will have to choose between two dominant and competing partners[105].

9. Domestic policy areas often identified as “world-class” or “world-beating” at least by politicians, are also relevant to “British exceptionalism”, especially when (as in the current COVID 19 crisis) they are identified as areas where the UK is superior to other nations. In this context health (including social care), education, infrastructure (especially road and rail) and justice (especially access to justice, the functioning of the criminal justice system, including prisons, youth detention centres and immigration holding centres) are in my view all relevant. The increasing pace and momentum of social change in all countries in all these and other areas, appears to me to call for a lower-key and comparative approach to national policy than is currently the case in the UK.

10. Three other “pillars” of the UK “system” seem to me to be relevant in considering “British exceptionalism”, in comparison with former EU partners and more generally. These are the UK’s democratic model and the rule of law; the military and the Civil Service.

11. During the UK’s membership of the EU, criticisms have been voiced about the alleged undemocratic nature of the EU and the fact that, in some Member States, respect for EU law is less than reliable. In the UK, Westminster has been seen as the “Mother of Parliaments” and the UK as the leading proponent of the “rule of law”. The prolonged Parliamentary stalemate in the Brexit process and recent events in the UK[106] and around the world show that no single State has a monopoly of virtue in these areas.

12. As far as the UK military is concerned, the superb response of the Army to the COVID 19 crisis is only one example of the professionalism of all three armed services. However, security and defence are an integral part of any country’s international role, including action to confront the rapidly-changing nature of warfare. The withdrawal of the UK from the (still embryonic) EU defence and security policy structure, weakens the country’s contribution not only to EU activities, but also to NATO and to peace-keeping activities around the world. In these areas, for EU Member States, the EU’s role is complementary and not competitive. The future size, capabilities and strategic purpose of the UK military can only be addressed in the context of a clear and credible foreign policy – starting in Europe – which still remains to be defined post-Brexit.

13. Finally, the UK has always boasted of a “Rolls-Royce” Civil Service. The regrets expressed in the EU at the loss of UK expertise in all the institutions, agencies and committees of the Union testify to the continuing excellence of the Civil Service as a whole. Nonetheless, the impact of politics, politicians (especially Ministers) and their political advisers[107]– together with the attractiveness of careers outside the public sector – have had a negative (and sometimes demoralising) effect on the UK administration. Here also, it would seem ill-advised at this time always to assume that the UK necessarily leads the world.[108]

Conclusion – what future for the UK by 2045?[109]

It was clear four years ago when Cameron decided to call an “in-out” referendum on the UK’s EU membership (in order, primarily, to unite the Conservative Party), that a “final” decision on “Europe” would be an important milestone in the country’s history. Cameron fully expected a positive vote on 23 June 2016. A narrow victory for the “Brexiteers” (with 2-3 million UK citizens living abroad or in the UK’s overseas territories being ineligible to vote)[110] has underlined:

- The sharp divisions and inequalities – between regions as well as social groups or classes – in the UK[111];

- Dysfunctional aspects of the UK constitution;

- The absence of a “Plan B”, as an alternative to EU membership, which is realistic (i.e. negotiable) and capable of guaranteeing an international political role and economic prosperity at least equal to that enjoyed by the UK as an EU Member State.

The unprecedented COVID 19 pandemic, affecting every sector of national (and international) life, not only makes infinitely more difficult the resolution of the UK’s negotiations with the EU and other prospective partners. It is also likely to dominate domestic politics for years to come, with the impact on health, social, education and especially economic policies aggravating existing challenges in these and other areas.

Against this background, a definitive and long-term solution to the UK’s relations with the EU and with other strategic partners around the world takes on an entirely new dimension. At the time of writing, it is difficult for me at least to envisage either:

- The structure and content of the UK’s relations with the EU and other key partners between now and 2045; or

- Changes in the constitution and governance of the UK itself between now and 2045, especially as regards the status of all four “nations” in the UK and at least some overseas territories, perhaps notably Gibraltar and the Falkland Islands.

As far as (a) is concerned, the most likely outcome in the absence of a radical change in the UK’s attitude to its negotiations with the EU, would in my view be a pragmatic series of sectoral agreements on the Swiss model. As far as (b) is concerned, it is in my view likely that the next 20 years or so will see the reunification of Ireland in the EU. For many of the same reasons which complicate the separation of the UK from the EU after 46 years, the independence of Scotland poses political and legal issues of an entirely different order. On the other hand, it would be surprising if the constitutional relationship between Gibraltar and (especially) the Falkland Islands remains unchanged over the next 20-25 years.

As one writer has said of the link between the current negotiations and British exceptionalism:

“Either way, there will be nothing heroic about the outcome. British exceptionalism has run its course. The coming years will demand nothing so much as a long, unremitting slog to rebuild the economy after the ravages of the pandemic and the collateral damage promised by Brexit.”[112]

Somewhat ironically, remembering that the UK’s withdrawal from the EU was in order to “take back control” and taking account of the way in which international power politics have evolved even since the 2016 referendum (the continued rise of China, Trump’s United States etc.), it seems to me that the future of the UK between now and 2045, will be shaped as much by forces beyond the UK’s control as by the UK itself. Far from “making Britain great again” and the Kingdom more “united”, thereby enhancing the sovereignty, autonomy and independence of the UK, the combined effects of Brexit and the COVID 19 pandemic may well underline the dependence of the UK on the goodwill – which can only come from mutual trust and respect – of partners around the world, starting with Europe. In this “brave new world” of unprecedented uncertainty[113], it seems to me that the closest cooperation and “solidarity”[114] with neighbours, friends and allies would at least be a starting point. If this is right, history will surely judge the UK’s self-isolation from Europe badly.

ALASTAIR SUTTON, 23 June 2020

They are from panels of the stunning main entrance door of the Bar Library in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

[1] Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Council President Charles Michel and European Parliament President David Sassoli.

[2] The UK is the 6th biggest economy in the world.

[3] I say “political” because not all the issues in the UK-EU negotiations are economic – security policy, civil and criminal justice cooperation, foreign and defence policy are examples of crucial areas where a framework for close cooperation must be devised.

[4] Which, given the exclusive competence of the EU under Article 207 TFEU, would only require the consent of the European (and not national) Parliament. On the other hand, negotiations on agriculture and food are always complex and sensitive. Now, especially given the UK’s parallel negotiations with the United States, the resolution of issues such as food safety and subsidies are likely to be uniquely complex both with the EU and the United States.

[5] Note that the EU’s negotiating guidelines provide that “the negotiations will be conducted in a way that ensures parallelism among the various sectoral tracks of the negotiation”. (Council Doc. 5870/20 ADD 1 Rev 3 of 25 February 2020, para. 11).

[6] I refer in particular to the global ramifications of the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, including the civil unrest in the UK.

[7] Most recently on Friday 12 June 2020 at the second meeting of the Joint Committee by the UK Minister Michael Gove.

[8] In the absence of an agreement by the end of 2020, the UK may well not be in a position to apply its external trade regime in the absence of sufficient trained customs officials. This will not be the case in the EU, where the common external trade regime will apply to the UK.

[9] Just one of many misleading slogans used by the UK in general and Johnson in particular to distort and banalise the immense complexity of the process of disentangling 46 years of legal, economic and institutional integration.

[10] It is of course true that a “no deal” situation at the end of 2020 would prolong uncertainty. However, at least on the EU side, extensive preparations have been (and are being made) in all sectors to minimise the inevitable damage.

[11] As indicate above, for many on the European side with longer memories, the “road travelled” with the UK dates back far further than the referendum of 2016. This longer view does not encourage optimism!

[12] 29 June till 3 July in Brussels (“restricted round” of chief negotiators and specialised sessions); week on 6 July in London (chief negotiators, teams and specialised sessions); week of 13 July in Brussels (chief negotiators, teams and specialised sessions); week of 20 -24 July in London; week of 27 July in London (chief negotiators, teams and specialised sessions); week of 17-21 August in Brussels.

[13] See also Barnier’s criticism of the “tone” used by Frost in his letter to Barnier of 19 May 2020. Dislike of “tone” is no doubt mutual.

[14] Barnier’s concluding words.

[15] Roughly 250 on each side, comprising 11 Working Groups.

[16] Even with former “allies” of the UK such as the Nordics, the Benelux, Poland, Cyprus and Malta.

[17] This comes on top of the manner in which the UK conducted the Brexit process, marked by repeated delays, constitutional uncertainty and the absence of any credible or viable alternative to EU membership.

[18] These are particularly acute of course on the border with the Irish Republic, where the Commission continues to have doubts about the UK’s willingness or ability to control goods, services and persons crossing the “internal” Irish border. The Commission’s request to establish an office in Belfast to monitor the implementation of the Irish Protocol attached to the Withdrawal Agreement was rejected by the UK.

[19] I underlined the shock which the UK would feel becoming a third country again after 46 years in my paper Negotiating Brexit for the UK Constitution Society in 2017.

[20] In fact since the Second World War, but especially since the referendum in 1975.

[21] The fact that the only UK President of the Commission (Roy Jenkins) played an important role in launching monetary union and that Vice President Arthur Cockfield (Baron Cockfield of Dover!) was in many ways the principal author of the Single Market is hugely paradoxical in 2020. At least the UK will have left a lasting legacy in the European Project through the contribution of these and other UK Commissioners!

[22] With Prime Minister Cameron’s failed attempt to secure a further derogation on the free movement of persons.

[23] Including the significant (risible) contributions by Boris Johnson as the Brussels correspondent of the Daily Telegraph.

[24] I use this term, even if at least the founding Member States certainly do not regard the Europe Project as an “experiment”.

[25] I was recruited by Barnier after my retirement to work on market integration in the African Union, using the EU Single Market project as a model. Barnier’s enthusiastic commitment to Africa shows the breadth of his international knowledge and interest.

[26] Perhaps especially those which have only recently recovered their full sovereignty after post-War domination by or incorporation in the Soviet Union!

[27] As opposed to the fantasy of “taking back control” espoused by the UK in the Brexit process.

[28] As demonstrated 3 years after the early completion of the Customs Union in 1968, in the landmark ERTA case in the CJEU.

[29] See for example the Singapore Opinion 2/15 of 16 May 2017

[30] Note that the term “fluid”, like “frictionless” has no legal meaning. The inescapable fact is (usually misunderstood in the UK, especially by politicians) that the abolition of physical, technical and fiscal barriers to the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital under Article 26(2) TFEU, ceased to exist in law for the UK on 1 February 2020, even if the effects of this legal change will only be fully felt from 1 January 2021 after the end of the transition period. From that time all the administrative formalities, delays and costs involved in cross-border exchanges will re-appear as a further burden (at the worst possible time in the wake of the COVID 19 economic crisis) for UK (and EU) economic operators.

[31] Note that the UK White Paper (CP226) of May 2020 on the UK’s approach to the Northern Ireland Protocol was recognised by the EU as a step in the right direction towards the watertight implementation of the Protocol, but leaving much technical work still to be done. Meanwhile, the UK has rejected the EU’s request to open an office in Belfast in order to monitor implementation of the Protocol – a move scarcely likely to increase trust in the EU.

[32] Frost refers to the EU-Norway agreement on fisheries, the FTAs with Japan and Canada, the aviation and nuclear agreements with “other third countries”.

[33] Frost refers to EU agreements or negotiations with Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Chile, South Korea and the US.

[34] Frost refers on financial services to the Japan agreement. On business visitors to CETA and Mexico.

[35] Switzerland, Norway and Ukraine are more integrated with the EU than the UK. The US has bigger trade flows that the UK with the EU, but the EU did not insist on the level playing field in TTIP.

[36] See for example the NAFTA.

[37] An implicit rejection of the UK’s “precedent-based” approach.

[38] I recall that in the EU’s negotiations with Japan in the 1970s and 1980s on “export moderation” in cars, electronics and machinery, where protectionist pressures in Europe were at their height and the EU exerted pressure on Japan to agree to measures outside the GATT, the personal and professional relations between the EU and Japanese negotiators were always courteous, even cordial. This was not the case in the 1970s, when similar protectionist pressures from the European textiles lobby (strongly supported by all EU Member States, but especially France) led to the acceptance by developing countries of the Multifibres Arrangement (MFA) and more than 30 bilateral “self-restraint” agreements. Here, both in the bilateral negotiations and in the GATT in Geneva, bitter resentment was felt by all the exporting countries of the EC’s use of “power politics”, threatening the very existence of the GATT in order to “persuade” the exporting countries to sign export restraint agreements. In my view, the resentment felt by developing countries has never been forgotten and was a major cause of the failure of the Doha Round.

[39] “Thanks” to David Frost and recognition of and “mutual respect” for the “professionalism” of both negotiating teams.

[40] I do not detect a great deal of respect in the EU (not merely the Commission) for the UK’s approach to Brexit in general, the Article 50 and current negotiations.

[41] 4 half days were devoted to fisheries (the EU’s pre-condition for any more general agreement including on trade in goods), 2 half-days to trade in goods, 3 half-days to services (and investments and other issues), two (only) on the LPF, 2 on law enforcement and cooperation, two on energy, one on “thematic cooperation”, one on social security, 2 on participation in Union programmes, one (only) on horizontal arrangements and governance, one on governance for LPF and open and fair competition, one on governance for aviation and one on LPF, open and fair competition and energy.

[42] One must assume that the accusation of bad faith on the UK side is an EU accusation and not one made solely by the Commission; still less by Barnier himself.

[43] Para.3

[44] Para.4

[45] Although these rules on state aids, social and employment law, as well as consumer, investor and environmental protection are currently set out in EU law to which the UK has agreed (or in many cases taken the lead in formulating), there is no legal reason why the UK may not seek other means of securing the same level of protection in the agreement with the EU. This would certainly require imagination and would not be easy – but it is at least negotiatble.

[46] Frequently contrasting its own attachment to the rule of law and access to justice with other Member States.

[47] As background on this issue, it is important to keep in mind that, from the EU’s perspective, the weakness (including lack of resources) of the UK’s customs authority was abundantly demonstrated in the Chinese textiles case. Here, following complaints by the French authorities and an investigation by OLAF, the UK were found to have under-valued textiles imports from China by around 2.5 bn. Euros, thereby causing a loss of this amount to the EU budget.

[48] Implying that, whereas the EU is prepared to move in an effort reconcile conflicting positions, the UK is not. In the absence of any negotiation by the UK, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the UK’s policy-preference at this stage is to enter 2021 without an agreement with the EU.

[49] Barnier said that on the ECHR there had been a “slightly more constructive discussion on the question of the commitment to the ECHR”.

[50] Not to mention, these days, a powerful and influential Parliament.

[51] As well, in the case of mixed agreements, of national and regional Parliaments.